In my role as a consultant advising fund managers on areas such as strategy formulation, operational efficiency and effectiveness, I've come across a number of situations where clients have attempted to do the "right" thing but in the process have caused unintended consequences

In a recent assignment I was asked to review a clients backdating policy looking at market best practice. Interestingly we found that there was little standardisation in the industry:

- Backdating standards vary between organisations dealing with managed funds vs superannuation products.

- Performance standards vary from T to T+10 business days.

- Varying levels of materiality are applied as a hurdle before applying compensation. Many organisation use a combination of basis points and dollar materiality.

- Compensation is generally made for the full backdating exposure (from effective date to processing date).

- Generally where transactions are processed outside performance standards compensation is made on a transaction basis with no netting applied.

Whilst I don't have all the answers I'd like to talk about some of the reasons for differences in approaches and how as practitioners we can deal with this issue.

What is Backdating

So let’s start with backdating. Backdating is applying a previously calculated unit price to a current transaction. Probably the easiest way to illustrate is by way of an example:

Day 0 Day 1 Day 5

NAV 1,000 1,010 1,060

Units on Issue 1,000 1,000 1,000

Unit Price 1.00 1.01 1.06

In this example we have a fund with issued units of 1,000 and a unit price that has steadily increased from inception at $1.00 to Day 5 at $1.06.

Now continuing with the example say on Day 0 an investor lodged an application for $1,000 however for some reason the application was not processed. The application may have been buried in someone’s in-tray, stuck behind another application, basically one of a thousand reasons why things don’t go as planned. So on Day 5 the lost application is found and is processed using the transaction date of Day 0; thereby using the unit price of Day 0 ($1.00). Assuming there are no other market movements on Day 6:

- The valuation would increase by $1,000 to $2,060

- The units on issue would increase by 1,000 unit to 2,000

However notice that the unit price has fallen from $1.06 to $1.03 although the market didn’t move. The drop in unit price is caused solely by the backdating of the transaction.

Day 5 Day 6 Day 6 (restated)

NAV 1,060 2,060 2,120

Units on Issue 1,000 2,000 2,000

Unit Price 1.06 1.03 1.06

In order to bring the unit price back to the correct level ($1.06) someone needs to compensate the fund to the order of $60 ($2,120 less $2,060).

So under what circumstances should compensation be paid to the fund and/or investor?

Reasons for Backdating

First, let’s look at some of the reasons for backdating.

Backdating occurs because we all operate in the real world. In a perfect world all applications, redemptions, switches, etc would be processed on the day they are received. There would be no peak volume days, staff shortages, system delays or any of the other 1,000 issues that can go wrong with registry processing.

Backdating is also necessary where processing errors have occurred and transactions need to be entered again. In these instances it is clear that the Scheme Operator should provide compensation.

Certain transactions by their nature will always cause a backdating impact. Each year funds suspend unit pricing while they calculate their annual distributions. Once the distributions are completed and unit prices calculated for the suspended period all the transactions that occurred during that period will be backdated. In some cases this can be up to three months. Additional those investors requesting reinvestment of their distribution would have that transaction backdated to 1 July. As we have seen backdating impacts existing unitholders and the question needs to be asked whether there should be compensation to the existing unitholders? It could argued that this delay is a structural issue of investing in managed funds however this still leaves the issue of not treating all classes of unitholders equitably.

There are a raft of other transactions that are typically processed at an earlier date than their transaction date. These include Advisor service fees, Contributions tax, Pension payments, Plan transitions, etc. In most instances there will be a large number of small transactions however the length of backdating can be substantial. When analysing these transactions you need to take into account the size of these transactions in relation to the size of the fund. The trick is defining what small actually is. Any backdating policy should reference these type of batched transactions and define a policy for compensation. Most operators we have come across review backdated transaction individually however these batched transaction are rarely mentioned in unit pricing policies.

Rules & Regulations

Moving on to the rules governing backdating. Firstly Section 601FC(1)(d) of the Corps Act provides that in exercising its powers and carrying out its duties, the responsible entity of a registered scheme must treat the members who hold interests of the same class equally and members who hold interests of different classes fairly. The issues with backdating are all about ensuring that incoming or outgoing members are treated equally with existing members.

The IFSA standards provide more specific guidance on backdating. Section 9.3 – you must consider the impact of transacting investors on the Scheme with consideration given specifically to the impact of backdating. Section 10.3 – Scheme Operator must have a backdating policy in place, documenting under what circumstances impacts of backdating will be funded by the Scheme Operator. Regardless of approach, the Scheme Operator must have a process in place to monitor the backdating of transactions and fund any unreasonable impacts as defined by the Scheme Operators policy.

So what is unreasonable? Standard No.17 provides some guidance that an unreasonable impact would be anything above the standard 30 basis points and/or $20. So two points come out of section 10.3:

- How do you monitor backdating transactions, and

- The definition of unreasonable impacts

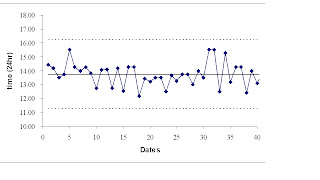

The monitoring of the level of backdating is going to depend on:

- The sophistication of your unit registry system, and

- Your relationship with the unit registry manager

As the issue of the unit price is the responsibility of the Unit Pricing department that department needs to have an insight into the level of backdating that is occurring, whether the function is internal or outsourced. As we will discuss later there are varying standards that can be applied in defining the parameters for backdating however this need to be based on actual facts, actual observations of how your business operates.

Lastly, we have the ASIC/APRA Guide to Good Unit Pricing Practice which states that the product provider should fund any backdating impact. Interestingly the guide does not differentiate between losses and gains arising as a result of backdating; however most operators are only funding losses.

Survey Results

Against this background in June last year we were asked by a client to undertake a short survey of the market practice in relation to backdating. The review surveyed a number of market participants offering a range of products across both retail and wholesale clients, with both in-sourced and outsourced administration. This is in no way a view of the whole market however it does give some insight into market practice.

So to the findings; and I’ll discuss these in more detail.

- Backdating standards vary between organisations dealing with managed funds vs superannuation products.

- Performance standards vary from T to T+10 business days.

- Varying levels of materiality are applied as a hurdle before applying compensation. Many organisation use a combination of basis points and dollar materiality.

- Compensation is generally made for the full backdating exposure (from effective date to processing date).

- Generally where transactions are processed outside performance standards compensation is made on a transaction basis with no netting applied.

Managed Funds vs Superannuation

Due to the greater paperwork requirements generally superannuation products have longer cutoffs for backdating than Managed funds. When you start looking at corporate super the timelines become even greater and can extend up to 3 weeks. The difficulty becomes determining who is at fault, the Product provider or the customer, if paperwork is not filled in correctly; and therefore who should compensate.

Performance Standards

From the survey we found that performance standards vary greatly ranging from T all the way up to T+10. Transaction processed outside this performance standard would be treated as an error and compensation would be applied. The organisations dealing with Wholesale funds could be reasonably guaranteed of meeting a deadline of T for processing all transactions however imposing this standard on a retail fund would be overly harsh. The difficulty with setting a backdating cutoff is that it:

- Must be based on facts. You need to review the level of backdating over the past 12 months and make an assessment. The cutoff cannot just be a catch all for slack processing standards.

- If the Product Issuer is funding all losses then a longer cutoff will reduce the instance of losses. There may be some pressure here from other areas of the organisation to have longer cutoffs.

Although there are differences in backdating cutoffs the most important aspect is to have a defendable position as to how you determined the cutoff. Again, this should be based on facts like an annual review of backdating trends.

As an aside this review of backdating trends could also be extended to other areas such as a review of:

Potential arbitrage – by identifying large trading or switching volumes. You could look at:

- Investors who have high dollar value of switches

- Investors who gain more often than they lose

- Investors who receive large dollar benefits from backdating

Potential fraud - for example where there is regular backdating by a particular operator

- Advisors who regularly switch all clients

- Efficiency measures. An increasing rates of backdating could highlight other issues such as staff shortages, lack of training, etc.

Once you have determined the cutoff for applying compensation you then need to determine the materiality level. In our survey we found Scheme Operators applying materiality of between 1 basis point and 10 basis points. The positive is that everyone is applying a tighter materiality than suggested in the ASIC/APRA Guide to Good Unit Pricing Practice. As with unit pricing tolerances it may be appropriate here to apply differing tolerance levels depending on the type of fund involved. Applying too tight a tolerance will result in multiple compensation claims and all the associated paperwork required.

Compensation

An important consideration in setting a tolerance level will be the level of sophistication of your unit registry system. It may be a fairly straightforward process to establish a policy where any transaction not processed on T receives compensation however then each transaction needs to be checked to see if it falls under or over the materiality level. Now it may seem like a simple calculation to divide the amount of the transaction by the fund size however if there is significant volume this will add to the workload especially if there is an involved good value claim process.

So the next area to look at is when does compensation apply from. Should it be from the original transaction date to the date it was actual processed? If you have a backdating cutoff of 3 days you would actually only need to compensate for the number of days less 3 days. From our survey we found that all participants were compensating from the date the transaction should have occurred.

So now to the big dollar question; will the backdating policy compensate just losses or will it treat gains and losses equally. I say it’s the big dollar question as this is the amount the scheme operator is going to be required to fund. There have been a number of instances where backdating policies have been set and at the end of the year the scheme operator has found that they have had to compensate substantially more than they had intended. Although you can undertake substantial analysis on backdating behaviours in the past, as they say in PDS’s, past performance is not guarantee of future performance. I would suggest that you test your policy under various conditions where the volume of backdating increases and assess the potential bottom line impact.

ASIC and APRA’s requirement is that investors are not negatively impacted however the Corps Act only requires us to treat all classes of investors equally. As a result if we are going to compensate investors for losses caused by backdating shouldn’t we also not allow then to benefit from backdating gains? Our survey found that no operators were compensating for gains as a result of backdating. This is understandable as if gains were taken they would need to held in reserve to offset any future losses.

Netting

And finally to netting. As I mentioned earlier all participants in the survey did not apply netting and analysed each backdated transaction. As a result you could have 2 backdated transactions on one day, one with a gain and one with a loss, the operator would have to fund the loss only.

If you did contemplate netting transactions it does throw up a number of issues for consideration:

Should profits be netted off against losses?

- Over what frequency should netting be applied (eg daily, monthly)

- At what level of granularity should netting be applied eg at transaction level / transaction type? by fund investment option? by fund sector?

- Should any other metric be applied to the netting eg checking materiality on the fund?

At first glance it would appear that backdating standards across the industry should be similar however there are valid reasons for differences. Any backdating policy must be supported by research of the level of backdating, say over the last 12 months.

There is always going to be tension between Risk and Compliance who will want tighter standards for backdating cutoffs and management who will want broader standards so compensation payments are lower. In order to assess the potential financial impact remember that the future doesn’t always replicate the past. In order to monitor the level and cost of backdating these should be reviewed monthly by both the Unit Registry and Unit Pricing Managers. As noted earlier most operators have adopted to only compensate backdating losses and not to apply netting. While this is a conservative approach offsetting backdating gains with losses could allow a tighter cutoff to be applied.

Finally, there are some unit registry systems that now allow automated backdating adjustments and provide a summary amount to be funded at the end of each days processing. Although these systems are efficient they need careful monitoring so the compensation amount does not exceed estimates.

In conclusion I hope I’ve provide some useful information and ideas that you can use.